Updated 17/2/25.

What is hypothermia and why is it Important?

The normal adult body temperature is about 37°C. Hypothermia is defined as a fall in core body temperature to 35°C or less. However, in the presence of trauma, even a fall down to 36°C is associated with increased mortality (death rate), so every effort must be made to keep all trauma casualties warm.

Hypothermia occurs when the mechanisms to prevent heat loss (described below) are no longer sufficient to prevent a fall in temperature below the level required for normal metabolism and bodily function. From a purely body temperature point of view, a casualty’s chance of survival is directly related to their core body temperature. The lower the body temperature, the higher the mortality. Although the lowest temperature from which someone has recovered is 13.7°C, few people who get that cold make a full recovery.

Overview of the Physiological Effects of Hypothermia

As the body temperature drops, metabolic requirements fall. The conscious level, heart rate, respiratory rate and breath size all decrease and when the victim is very cold (temperature 30°C or below), the heart rhythm may become irregular. These changes make signs of life difficult, if not impossible, to detect and in severe cases, can result in living casualties appearing to be dead. Unless there are other injuries incompatible with life, casualties without detectable signs of life who have severe hypothermia (see below for stages) should be managed as alive. This has given rise to the guiding principle – “not dead until warm and dead” and is discussed further below.

Whilst reduced core temperature is an overall threat to life, it does offer some protection from hypoxia. Brain metabolism decreases as the temperature falls below 35°C, so that when cold, it requires less glucose and oxygen, so can survive prolonged periods with a reduced blood supply without sustaining any damage. This includes periods of cardiac arrest, which would prove fatal in a normothermic (normal temperature) individual. As a guide, a normothermic brain will only survive 3-4 minutes cardiac arrest. By contrast, at 27°C, in a young person, the brain will tolerate about 15 minutes and at 14°C, about 40 minutes. The figures for a healthy person in their 60’s will only be about half those in the younger person.

How is Body Heat Lost to the Environment?

Understanding how heat is lost from the body will enable the rescuer to better appreciate how to care for a casualty, and also how to stay safer on the hills themselves. There are four mechanisms:

Radiation - the main route in a normal environment. It occurs when the ambient temperature is less than the body (which is almost always in the UK) i.e. there must be a temperature gradient. Heat loss by radiation can be reduced with a space blanket. However, if the casualty is already very hypothermic, a space blanket will be ineffective as there is very little body heat to reflect back.

Conduction – transfer of heat from the body by direct contact with other objects. Water conducts heat away from the body 25 times faster than air so wet clothing is particularly dangerous. This emphasises the importance of staying dry and explains why a wet person cools off so quickly.

Convection – the body heats air in contact with it. This air then moves away and is replaced by colder air, which in turn is heated up and then moves away. Thus, convection is the main mechanism of heat loss in windy conditions. A wind speed of 8 mph removes four times more heat than a wind of 4 mph. Heat loss by convection is reduced by insulation. Note that wool and synthetic insulation provides effective insulation when wet, unlike down, which does not.

Evaporation – this applies to fluids on the body surface (sweat, rain, etc.). This also illustrates the importance of staying dry.

Body Mechanisms to Prevent Hypothermia

The brain senses when the body temperature starts to drop and immediately initiates a series of responses that are intended to prevent a further fall and restore the temperature back to normal. These responses are behavioural (e.g. seeking shelter, putting on extra clothing, increasing exercise, and taking in sufficient food) and physiological (e.g. shivering, vasoconstriction). Exercise produces much more heat than shivering, particularly when large muscles are working.

Important note about the impact of exercise on cooling

We cool off more quickly when we stop after exercise unless we are adequately protected, for three reasons. This has important implications for the MR casualties.

Sweat is still present on the skin (see above).

Blood vessels in the skin are dilated to help remove excess heat during active exercise.

The person initially continues to feel warm so doesn’t put on additional clothing until they start to feel cool, by which time, their body temperature, which might have been slightly elevated during exercise, has not only returned to normal but has overshot and fallen below 37°C i.e. they have become mildly hypothermic.

Hypothermia in Mountain Rescue

In mountain rescue, hypothermia can be primary i.e. the only problem, or secondary to other injuries and diseases. It can occur at any time of the year, although severe hypothermia is more likely to occur as a primary condition during the colder months. Poor clothing, alcohol consumption, hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar) and exposure to water and wind increase the risk of it occurring at other times of the year.

Most casualties in the Lake District will be at least mildly hypothermic by the time we arrive

if they have been sitting still on the hill side, particularly in winter, or in the wind and rain,

without adequate protection.

Therefore, they should all be assessed for hypothermia, including measuring their temperature,

protected from the environment, and reassessed prior to hand over to another agency.

Practical Assessment of Hypothermia

Who is at risk?

Hypothermia is particularly likely in certain situations so expect it if any of the following are present:

Adverse weather conditions (cold, wet, windy)

Night time

Higher altitude. Hypothermia can occur at any altitude, but the higher the location, the lower the ambient temperature, the higher the wind speed, and the more energy that will have been consumed to get up that far.

Been out on the hills for a long time (which means they will have depleted energy reserves)

Been unable to move from their current location because of injury, no lighting, crag fast, etc.

Insufficient food

Very young or very old

Inadequate clothing

Inadequate protective equipment e.g. no bag or tent to shelter in

Reduced conscious level, particularly in the absence of trauma

Assessment – History

Consider the following:

The ambient temperature

Wind chill

Clothing/shelter

Length of exposure

Have they been insulated from the ground

Have they become wet

Time since they stopped exercising

Exhaustion

When and what they last ate or drank. This is not for SAMPLE, but will give an indication of how depleted their energy reserves will have become

Assessment – Clinical Features

Signs that hypothermia is only mild are:

Fully alert

Actively shivering

Able to walk

Indications in general demeanour and behaviour that things have deteriorated significantly are:

Impaired consciousness, particularly in the absence of trauma is a warning sign

Difficulty speaking, slow thinking and amnesia

Paradoxical undressing (the casualty feels hot and tries to take their clothes off)

Terminal burrowing (the casualty will enter small, enclosed spaces to shelter)

Physical signs on examination:

Shivering may be present or absent

Cold and pale skin

Decreased body temperature (see below)

Slow and or laboured movement, stumbling pace, inability to use hands

Decreased heart rate

Decreased respiratory rate

Decreased blood pressure

Measuring temperature using the ear thermometer

Why do we need to know the temperature in hypothermia?

There are three main reasons:

To help identify the cause of reduced conscious level. If the body temperature is 32°C or more and there is no trauma, then the cause of reduced conscious level is not hypothermia. So you need to look elsewhere e.g. hypoglycaemia, stroke, drugs, etc.

The risk of cardiac arrest increases when the temperature falls to 28°C and below.

In pure hypothermia, asystole (flat line on the ECG which means no heart activity) does not tend to occur until the temperature is <24°C. Therefore if the temperature is higher e.g. 30°C and asystole is present, the casualty may have had a normothermic cardiac arrest e.g. myocardial infarction; avalanche; drowning, before cooling. These people may not benefit from prolonged resuscitation attempts. The Alpine practice in casualties with asystole is to look for evidence that significant hypothermia was probably present before cardiac arrest occurred e.g. lightly dressed casualty (in our area, an example would be a Fell runner).

Which temperature is important?

In hypothermia, the most important temperature reading is also the hardest one to measure. We need the core body temperature, which essentially is the temperature around the heart, since this governs whether or not a cardiac arrest is likely to occur. In hospital, this is done by inserting a temperature probe either into the oesophagus, or alternatively along a major vein and passing it into the heart. Clearly, these are impossible in MR so we have to use an alternative site. The only thermometer that has been shown to be accurate in studies is a special type of ear thermometer, but this is not currently available for prehospital use in an easily-portable form. Therefore, we use an infrared ear thermometer, as this is the least inaccurate of the non-invasive methods available. It will read down to 20°C, and if used correctly, it will read to within ±2°C, which is accurate enough for our requirements.

For information, the following are either too inaccurate in hypothermia or cannot be easily used in a prehospital situation:

Armpit (axilla)

Rectal

Oral (we trialled this method, but there are no published validated studies that indicate that oral temperature is accurate enough, which is why we have abandoned its use).

Measuring body temperature using the Braun Thermoscan Pro 6000 infrared ear thermometer

The thermometer is in the Monitoring pouch in the Medical Sack. A photo of the device and the cradle is shown on the right.

We carry the thermometer mounted in the cradle as this protects the sensing tip from buffeting. A box of probe covers is also there (see figure 1).

We can minimise the error by using the thermometer correctly.

Preliminaries

The sensing tip should already be clean, but if in doubt, wipe it with a soft cloth or alcohol wipe (see video below which shows this nicely).

It will under-read if the device becomes cold, which it will be after having been stored in a rucksack. Therefore, put it in your pocket for 10 minutes before use.

It will also read low if the ear canal is full of snow or cold water, so while the thermometer is warming up, if the casualty is conscious, ask them to gently wipe the ear with a hankie or similar. Put a hat on the casualty if they haven’t already got one on, and make sure it covers the ear canal on both sides of the head so you can use both if necessary. This will allow the air inside the canals to warm up to body temperature.

If the casualty is in a group shelter, that will improve accuracy since it also under-reads if the face is cold

Using the thermometer

This is shown in the video below. The main points are:

Explain to a conscious casualty what you wish to do, how you will do it and get their verbal consent.

Take the thermometer out of the cradle

Push a disposable probe cover over the sensing tip. It click when it is correctly in place.

Gently put the thermometer tip into one of the casualty’s ear canals until you feel resistance. It isn’t necessary to push hard. Consider that you are aiming the tip very slightly in front of the opposite ear (see figure 4)

NOTE: you need to introduce the thermometer until it stops so that the sensing tip is as close to the ear drum as possible. This is important because there is a temperature gradient of about 2-3°C along the ear canal (figure 5), so the further out the tip is, the more it will under-read.

When you are happy with your position, wait for about 10 seconds for it to equilibrate and then press the button to take a reading. You will get a result in about 5 seconds.

Record the reading and repeat the process using a fresh probe cover. Although theoretically, you could re-use the cover that had just been used because you are using it on the same person, it could have picked up some ear wax, which will make the reading less accurate. Therefore, use a fresh cover.

Keep taking measurements until the readings you get are ideally within 0.5°C (certainly within 1°C) of each other.

If you’re not sure about one ear, try the other.

NOTE: our thermometers do not measure below 20°C. They register a lower temperature as ‘Lo’, and they also will do that if the sensor is cold (see above).

Thermoscan Pro ear thermometer

Fgure 1

Box of probe covers

Figure 2

Single probe cover

Figure 3

Thermometer in the ear for measuring the temperature

Figure 4

Temperature gradient along the ear canal

Figure 5

UNDERSTANDING HYPOTHERMIA: 1 TERM, TWO PHYSIOLOGICAL STATES

The situation is summarised in the slide below.

In mild hypothermia, the victim essentially behaves as normal. They can take steps to look after themselves, vital signs are normal and the body still has the capability to compensate and move the temperature back towards normal. These cases are easy for us to care for. It is important to remember that mild hypothermia is only a narrow window of 4-5°C, so it is essential to act quickly to prevent further deterioration.

By contrast, severe hypothermia is the world of extreme physiology. Vital signs are extremely deranged and may be undetectable without a medical monitor, or absent. In order to survive, these people need special care from the moment they are found.

The bit in the middle is the transition stage between the two extremes and is termed Moderate Hypothermia. Although usually between 32°C and 28°C, when the change actually starts in any individual depends on what else is going on, as described in the slide. In this stage, compensation mechanisms are failing rapidly, shivering tails off, mental state becomes increasingly impaired and the victim becomes unable to perform even simple tasks or make easy decisions e.g. route choices. We have seen this in some very sad MR rescues that didn’t end well. In moderate hypothermia, the likelihood of a hypothermic arrest starts to increase dramatically.

Severity of Hypothermia

In order to decide upon the appropriate clinical management and where the casualty should be evacuated to, we need to determine the severity of the hypothermia. This is done using the ICAR MEDCOM scale (International Commission for Alpine Rescue), which is used internationally. The stating system indicates how likely it is that the casualty will have a hypothermic cardiac arrest.

It has been shown that conscious level falls predictably as body temperature falls. Therefore in the absence of any other causes of reduced conscious level e.g. hypoglycaemia, drugs, alcohol, etc., a fully conscious person will not have a cardiac arrest due to hypothermia (NB they can still have one for other reasons), whereas someone who is only ‘V’ or ‘U’ on AVPU is very likely to arrest.

Knowing if an arrest is likely is very important information for several reasons:

A hypothermic arrest makes our management on the hill and evacuation much more challenging

There are fewer hospitals equipped to deal effectively with a hypothermic arrested casualty

Rewarming is much more difficult in hospital

The ultimate prognosis is worse if the patient arrests

If using ACVPU instead of AVPU, then the Staging system is slightly modified as shown below.

MREW Hypothermia Protocol

There is one protocol to guide management and separate Explanatory Notes.

Essentials of Management

In practice, and for simplicity, there are only two categories of hypothermia we need to worry about:

Mild hypothermia in a low-risk casualty

Everything else

The management is summarised in Casualty Care Revision in Mountain Rescue.

ASSESS THE SEVERITY OF HYPOTHERMIA

Base this predominantly on the symptoms and signs:

Shivering/not shivering

Conscious level

Pulse rate

Presence of trauma

Temperature

The importance of hypoglycaemia

Hypoglycaemia is very important because it prevents the body rewarming by shivering, and will also limit how much someone can move around to warm up.

Even people who are not diabetic can become extremely hypoglycaemic if the conditions are right.

It’s not uncommon after extreme exercise, but there are other causes too e.g. alcohol. We had a rescue on Blea Rigg in 2015 in which the casualty, a 25-year-old man, had a BM of 2.5, just from severe exercise. A neighbouring MRT (Jan 2025) was called to an unconscious hypothermic man. They don’t measure BM so gave him glucogel just in case and he started to wake up. The casualty’s BM was checked in the ambulance and was about 2.3, so when the MRT arrived, it must have been lower than that. It turned out that he was mildly hypothermic (temperature in low 30’s) and had been drinking a lot of alcohol.

Checking for signs of life in the apparently dead person

People with severe hypothermia may be unconscious, and be breathing very slowly and have a very slow pulse e.g. 4 breaths per minute; irregular and shallow, with a pulse rate of <10/min. You can use the Propaq or Viatom monitors to determine the presence of cardiac activity using ECG.

If the ECG shows regular similar-shaped squiggles, this means that the heart is working so do NOT start CPR, regardless of how slow the pulse rate is. Assume that the casualty is still alive, regardless of whether or not you can feel a pulse or detect that they are breathing. In extreme hypothermia, the brain can survive with a very slow heart rate.

If the breathing is sustained, this means that blood is reaching the brain and THEY ARE ALIVE

DO NOT BE TEMPTED TO START CPR

If you start CPR, you will actually cause the heart to stop and any blood flow to the brain will immediately stop, making the patient totally dependent on the quality of your CPR.

If in doubt, unless there clearly are injuries that are incompatible with life, remember they are not dead until warm and dead!

DECIDE WHICH GROUP THE CASUALTY IS IN

Mild Hypothermia in a basically well person (low risk)

Normal conscious level

Shivering

Pulse steady and in normal range

No trauma

All other cases (medium to high risk)

Even if the temperature is in the ‘mild’ range, the presence of any of these factors will increase the risk by reducing physiological reserve. These casualties need more careful handling

Reduced conscious level / unconscious

Shivering minimally or stopped

Abnormal respiratory and pulse rates

Trauma

Temperature <32°C

Unable to care for themselves

History of inadequate food intake

Older people (possibly >60, depending on fitness; certainly >70y)

Presence of concurrent medical conditions e.g. diabetes

Children (the smaller they are, the more vulnerable they are)

TREAT APPROPRIATELY

MILD HYPOTHERMIA is not life threatening

Shelter. Use a group shelter whilst assessment and any treatment is ongoing. Get three or four people inside the shelter to provide warmth and ask others to hold it down from the outside.

Insulate from the ground

Exchange wet clothes for dry, if possible

External heat won’t speed up rewarming if they are already shivering a lot, but it is comforting for them. It will also reduce the amount of shivering, which is useful if they have got behind on the amount of food they have taken in.

Give lots of food and a warm drink (avoid caffeine & alcohol)

Get them moving once they have refuelled and recovered

These people will continue to warm when they start moving and can go on their way once they have rewarmed and got down to a place of safety.

Proper use of a group shelter

MODERATE & SEVERE HYPOTHERMIA are life-threatening, and the colder they are, the more this is so.

Follow the MREW Severe Hypothermia Protocol. There is a copy in the Cas Card folder and in the AutoPulse battery rucksack.

The main points are summarised here.

Issues

The casualty is still alive

They have a significant level of hypothermia

If the temperature falls to below 30°C, they cannot rewarm themselves, and are at increasing risk of a cardiac arrest

All casualties in this category should go to hospital, even if there is no trauma

Practical considerations

Handle very carefully to avoid causing a cardiac arrest if the conscious level is reduced or temperature is <30°C

Shelter

Insulate from the ground

Do not worry about exchanging dry clothes for wet. Doing this involves too much movement of the casualty, and if they are cold enough, this could cause a cardiac arrest.

Apply heat to the front of the chest and the armpits only (never to the limbs or the back with the casualty lying on them). Put the pads on top of a layer of clothing. Ready-Heat pads are stored in the Cas Bag rucksack and the small Fracture Sack. They need to be exposed to air to start them heating up.

It can cause a burn.

Package the casualty plus heat pads in the ‘Blizzard’ blanket (big metallised reflective blanket, stored in the Cas Bag rucksack’s front pouch). Before closing the blanket around the casualty put any extra insulation on top of that first. Then zip up the Cas Bag (see photo for the layers of insulation). Packaging is discussed further below.

Plan for cardiac arrest (increasingly likely the colder they are)

Arrange for AutoPulse to be available in case a cardiac arrest occurs

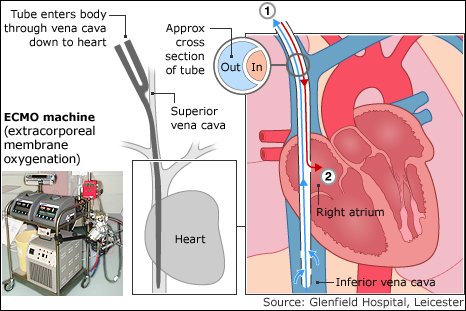

People with severe hypothermia are likely to need rewarming with a heart-lung machine (ECMO). This is only available in specialised centres. In relation to the Lake District, the two centres providing this facility are in Newcastle and Manchester. Transport there would have to be by air.

Ready-Heat pads are vacuum packed

Cardiac arrest in severe hypothermia

Important

The likelihood of being able to successfully resuscitate a hypothermic casualty who has had a cardiac arrest is almost zero. Once a severely hypothermic person is in asystole, it is extremely unlikely that a cardiac rhythm of any sort will re-emerge until the heart is rewarmed. Therefore, you must do everything in your power to prevent cardiac arrest from occurring.

Packaging and minimising further heat loss

When body temperature is below 30°C, you must balance the risks of removing the clothing (increased cooling during removal or triggering an arrhythmia if the body is handled roughly) against leaving wet clothing in place. Expert opinion suggests it is safer to leave wet clothes in place until the casualty is in hospital where it is warm.

If you do decide to replace wet clothes with dry, do not do it on an open hillside. Only consider it in a group shelter with four or more rescuers and after the temperature inside has warmed up and stabilised. Do not undress in the conventional sense but carefully cut off the clothes, removing them a bit at a time rather than all at once to minimise further cooling and reduce movement of the casualty. Insulate with dry clothing.

Heat packs will reduce further cooling. They are not to start rewarming in the field.

Wrap in an occlusive sheet (we are using the ‘Blizzard’ Blanket) and seal around the openings, ensuring access where necessary. Once the atmosphere inside the enclosure is fully saturated with water vapour, no more heat can be lost by evaporation from the skin, which is the major route of heat loss in this situation.

A reflective blanket has little additional value over a heavy duty plastic bag as virtually none of the heat loss is by radiation because the skin temperature is so low. However, a reflective blanket may be of value when heat packs are in place by helping to keep the heat from those inside the enclosure.

Finally wrap in the Cas Bag.

How to use heat pads

Expose to air for 15 minutes to allow them to warm. For expediency, this can be done as you leave the vehicle/during the approach.

Place heat pads around the chest and armpits only, not the limbs or the back. Do not worry about, or attempt to rewarm, the peripheries. Warming the limbs can have undesirable effects including triggering an arrhythmia.

Do NOT place heat pads directly on the skin. They will cause a burn in hypothermic patients. Place them on top of a layer of clothes. For example, if laid on top of a wet base layer, this will warm up over about 15 minutes or so and the heat will pass to the patient.

Casualty handling and positioning

Handle the casualty extremely carefully as a sudden shock can precipitate a cardiac arrest.

Avoid raising the legs and arms. If the legs are raised, the sudden influx of cold blood from the legs into the core will cool the heart and can cause life-threatening arrhythmias.

Keep the casualty horizontal. If they are to be winched into a helicopter, insist that they are winched on a stretcher to ensure they are kept horizontal. If horizontal is not possible, slightly head up is marginally safer than head down because with head down, cold blood will return from the legs and further cool the heart.

Airway management in severe hypothermia

Start medium flow oxygen(6L/min)

When evacuating by stretcher and the casualty is not breathing, it is only possible to breathe efficiently for the casualty if you insert an i-Gel and ventilate with a bag-valve.

Squeeze the bag gently at a rate of about 6 breaths per minute.

Monitor for cardiac instability

Connect the Propaq. Monitor continually in case a cardiac arrest occurs. It doesn’t matter whether you have been taught about ECG’s. The interpretation is very simple in these cases. If you get regular similar-shaped squiggles on the display e.g. at 20/min (the monitor displays the rate), you know you have got acceptable heart function. If it becomes a flat line or a haphazard wave form, that’s a cardiac arrest. Always do a snapshot so that you can show it to someone who can read ECGs.

CPR in severe hypothermic cardiac arrest

If you are sure that a cardiac arrest has occurred, the ideal management is to deliver continuous CPR until the casualty reaches hospital and is being rewarmed with the ECMO machine.

If defibrillation is required, do not attempt it more than three times. This is because at temperatures below 30°C, the heart is usually resistant to defibrillation until the heart rewarms. Multiple attempts at defibrillation whilst the heart is cold will be ineffective and will injure the heart muscle.

Call for the AutoPulse immediately. Only team members who have been trained to use it should do so. Everyone else must only do manual CPR.

DELAYING THE START OF CPR

If you witness a hypothermic cardiac arrest (e.g. the patient is connected to the Viatom monitor and you observe or it records the ECG change from a normal-looking rhythm to an abnormal rhythm e.g. ventricular fibrillation or asystole (flat line), you do not have to start CPR immediately if delaying a few minutes would enable the casualty to be moved to a safer location e.g. out of a stream, off a ledge, or away from where an avalanche has just occurred (in case of a secondary avalanche). You have up to 5 minutes before you need to start CPR.

INTERRUPTIONS TO CPR

Once you have started CPR, the ideal is to continue it until the casualty reaches hospital and is being rewarmed with an ECMO machine. The best way to achieve this is with the AutoPulse. If the AutoPulse is not available or it breaks down, you will have to resort to manual CPR.

There may be occasions during an evacuation when it is physically impossible to deliver good quality manual CPR e.g. during a steep descent, when moving the casualty on the stretcher, etc. In these situations, it is permissible to interrupt CPR periodically. The aim will be to deliver at least 5 minutes uninterrupted manual CPR and then stop chest compressions for a period whilst you move further off the hill.

Note that the fact that CPR should be uninterrupted does not mean it has to be carried out by the same person (see below).

DELAYED AND INTERMITTENT CPR TIMES: ‘5 on; 5 off’

For a witnessed hypothermic cardiac arrest, you can delay start of CPR by up to 5 mins

Try to start CPR as soon as is practicable and do at least 5 mins uninterrupted CPR

If necessary, CPR can be interrupted again for up to 5 minutes before it must be resumed.

Resume continuous CPR as soon as feasible

FOR ALL OTHER CARDIAC ARRESTS, CPR MUST BE IMMEDIATE AND CONTINUOUS.

Changing rescuers to ensure high-quality CPR

Delivering chest compressions is exhausting. Studies have shown that by two minutes, CPR efficiency, as shown by rate, regularity, and depth of compression, will have dropped dramatically. Therefore, change rescuer every 2 minutes. If someone is getting tired before the two-minute period has elapsed, change rescuer at the next opportunity i.e. when the next two rescue breath are delivered.

Referral To ECMO

Once in cardiac arrest, your chances of resuscitating a severely hypothermic casualty are small. The casualty will need to be rewarmed before any type of cardiac rhythm can return. Specialist cardiac support will be required to rewarm them effectively and maximise their chance of survival.

ECMO Centres

Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester

Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle

Alder Hey Children’s Hospital

These phone numbers are all included on the Hypothermia Protocol so you can contact them about direct admission. ECMO is a complex and very expensive undertaking. When you call, you will be asked a series of questions as they try to ascertain whether the casualty is a good candidate for ECMO.

The ECMO referral form (below) has been developed to include the key questions they are likely to ask you and is carried in the hypothermia sac and AutoPulse battery sack so you can ensure you have the answers prepared when you call.

The video below is an amazing story about the Praesto Fjord incident in Denmark, in which seven teenagers were immersed in ice cold water following a boating incident. All were rewarmed with ECMO and all survived and made a good recovery. It reminds us why we do what we do. Seven young adults are alive because someone didn't give up just because they appeared to be dead.